Be Specific About Containing Books The Missing of the Somme

| Title | : | The Missing of the Somme |

| Author | : | Geoff Dyer |

| Book Format | : | Paperback |

| Book Edition | : | Anniversary Edition |

| Pages | : | Pages: 176 pages |

| Published | : | May 1st 2003 by Phoenix (first published December 31st 2001) |

| Categories | : | History. Nonfiction. War. World War I. Writing. Essays |

Geoff Dyer

Paperback | Pages: 176 pages Rating: 3.9 | 639 Users | 98 Reviews

Narrative In Pursuance Of Books The Missing of the Somme

”Crosses stretch away in lines so long they seem to follow the curvature of the earth. Names are written on both the front and back of each cross. The scale of the cemetery exceeds all imagining. Even the names on the crosses count for nothing. Only the numbers count, the scale of loss. But this is so huge that it is consumed by itself. It shocks, stuns, numbs. Sassoon’s nameless names here become the numberless numbers. You stand aghast while the wind hurtles through your clothes, searing your ears until you find yourself almost vanishing: in the face of this wind, in this expanse of lifelessness, you cannot hold your own: you do not count. There is no room here for the living. The wind, the cold, force you away.”

Notre Dame De Loretta, French cemetery

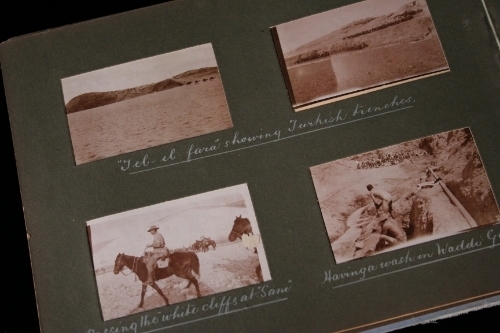

It starts, really, with an old photo album. One that may be found in a battered trunk in the attic or tucked away in a musty cupboard.

”Dusty, bulging, old: they are all the same, these albums. The same faces, the same photos. Every family was touched by the war and every family has an album like this. Even as we prepare to open it, the act of looking at the album is overlaid by the emotions it will engender. We look at the pictures as if reading a poem about the experience of seeing them. I turn the dark, heavy pages. The dust smell of old photographs.”

Geoff Dyer realizes that he passes by a World War One cenotaph every day; and yet, hadn’t really seen it in decades. It happens with everything that we see frequently. We stop seeing it. The only way we would be shaken out of our apathy is if it were suddenly missing, a hole in our vision that we know something is supposed to be there. When Dyer looks through the old family album and sees the pictures of his grandfather in uniform he really begins to notice the cenotaph for the first time. That afternoon spent thumbing through that album, hearing the crackle of stiff paper as if he were wedging open a creaky door to the past, inspires him to know more about his grandfather’s war. It sends him on a mission travelling around England, France, and Belgium visiting the monuments for the war.

For the first time he really thinks about war, not just The Great War, but all wars.

”After The Great War people had little clear idea of why it had been fought or what had been accomplished except for the loss of millions of lives. This actually made the task of memorializing the war relatively easy.”

”The issue, in short, is not simply the way the war generates memory but the way memory has determined — and continues to determine — the meaning of the war.”

”Men no longer waged war, it has often been said; war was waged on men.”

Dyer appreciates the sculptures, the monuments, the memories that artists tried to immortalize out of metal and rock, but…

”Although many had the talent, no British sculptor — not even Jagger — had the vision, freedom or power to render the war in bronze or stone as (Wilfred) Owen had done in words.”

Jagger’s Royal Artillery Sculpture

”Down the close darkening lanes

they sang their way

To the siding-shed …

Ernest Brooks’s iconic photo of World War One

But really how about more Owen

Their breasts were stuck all white with wreath

and spray

As men’s are, dead.

Is a picture worth a thousand words when the words are such as these?

”[I saw his round mouth's crimson deepen as it fell],

Like a Sun, in his last deep hour;

Watched the magnificent recession of farewell,

Clouding, half gleam, half glower,

And a last splendour burn the heavens of his cheek.

And in his eyes

The cold stars lighting, very old and bleak,

In different skies.”

It is hard not to think of The Great War as a war without color. It is caged in black and white film, and even though we know that blood was red not grey, and that the same blue skies, and the same green grass, and the same brown mud existed then as it does today; it is still difficult to conjure up those images without the color leached away.

The world had had the colour bombed out of it. Sepia, the colour of mud, emerged as the dominant tone of the war. Battle rendered the landscape sepia. ‘The year itself looks sepia and soiled,’ writes Timothy Findley of 1915, ‘muddied like its pictures.’

As a writer it is hard to convey something as horrible as war without reducing the impact with the very adjectives and conceptions that we use to articulate the very nature of the horror. Describing war becomes the equivalent of a slasher film where the gore is not as shocking as it is entertaining.

”War may be horrible, but that should not distract us from acknowledging what a horrible cliché this has become. The coinage has been worn so thin that its value seems only marginally greater than ‘Glory’, ‘Sacrifice’ or ‘Pro Patria’, which ‘horror’ condemns as counterfeit. The phrase ‘horror of war’ has become so automatic a conjunction that it conveys none of the horror it is meant to express.”

Gassed by John Singer Sargent

This is a book full of cerebral reflections about the war. Dyer ties in art and literature, evoking the likes of Sargent, Fitzgerald, Sassoon, Owen, and Isherwood to make his points. He discusses the impact that the ill fated Robert Falcon Scott expedition had on the World War One generation.

“By now the glorious failure personified by Scott had become a British ideal: a vivid example of how ‘to make a virtue of calamity and dress up incompetence as heroism’.”

The commanders exploited and relied on the Scottesque inspired brainwashing that made men believe that dying for their country, even so imprudently as they were asked to in the great war, was heroic. The betrayal of that childlike innocence in such a monstrous fashion was beyond irresponsible, and bordering on criminal.

Dyer makes one final stop at Beaumont-Hamel cemetery and leaves with more hope than despair.

”I have never felt so peaceful. I would be happy never to leave. So strong are these feelings that I wonder if there is not some compensatory quality in nature, some equilibrium — of which the poppy is a manifestation and symbol — which means that where terrible violence has taken place the earth will sometimes generate an equal and opposite sense of peace. In this place where men were slaughtered they came also to love each other, to realize Camus’s great truth: that ‘there are more things to admire in men than to despise’.”

Itemize Books Conducive To The Missing of the Somme

| Original Title: | The Missing of the Somme |

| ISBN: | 1842124501 (ISBN13: 9781842124505) |

| Edition Language: | English |

Rating Containing Books The Missing of the Somme

Ratings: 3.9 From 639 Users | 98 ReviewsCriticism Containing Books The Missing of the Somme

I tried to finish this, I really did. I was assigned this book for one of my classes. Honestly, WWI history doesn't fascinate me *that* much, but I went into it without any expectations or pre-knowledge of the plot. This book has many gold nuggets of beautiful writing, of information, critical analysis, art history, but as a whole, for some reason it just felt hard to get through (I'm sensing a trench metaphor here). While I understand that this book is part critical essays, part travelogue, itThis is fine, and has a lot of interesting stuff about how the war was being pre-emptively remembered or prepared for remembrance even while it was still ongoing. But is there some kind of clause in British publishing contracts mandating that all WWI books must end with some kind of sober, solemn reflection? Even when the previous 120 pages took a much more scholarly, analytical and sometimes cynical view of the matter? "I have never felt so peaceful," Dyer declares, wrapping the book up with a

The Great War and Geoff Dwyer made fine companions during the pandemic. The unimaginable horror of that war to end all wars that almost ended civilization and forever marked a line between the past and modern times, is explored as travelogue to memorial sites and through art and poetry that speaks to memory and how slippery it is.

Wanted to like this but found it hard reading. Made it through it because it was relatively short. Still trying to figure out what all those who gave it such wonderful reviews got out of it that I missed. I wanted it to be more of a travelog - when the author visited battlefields and memorials, it was interesting and well written. But the literary references and discussions, something I normally enjoy, were tedious and obscure.

A fine meditation on memorials for the dead of the Great War and how we construct the memories we hope to fix into stone or bronze. Dyer's essay grows out of Paul Fussell's work in "The Great War and Modern Memory" but stands very much on its own. Dyer is less interested in the literary antecedents of Great War literature than in the concrete ways England tried to hold on to a memory of the war and its losses. His account (this would be in the early 1990s, a decade or so before the issues of

This book is tough to categorize which is another way of saying that I'm not exactly sure I understand what the focus was. It's an odd book that includes some travel memoir that is interesting. There is a lot of time spent thinking about the structure of WWI memorials and what they should look like that was also quite interesting.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.